Summit, New Jersey, a bedroom community to New York City, will begin subsidizing Uber rides for residents traveling to and from the local train station starting Monday — a move the town initiated to avoid building a new parking lot, a multimillion-dollar effort. For Uber, the partnership is another step in a series of strategic moves to extend its reach to the suburbs.

Summit has a population of about 22,000 and its own NJ Transit Rail Station, which is a 45-minute ride from New York’s Penn Station. When Michael Rogers became Summit’s city administrator about a year ago, he noticed that most everyone complained to him about parking, he told BuzzFeed News.

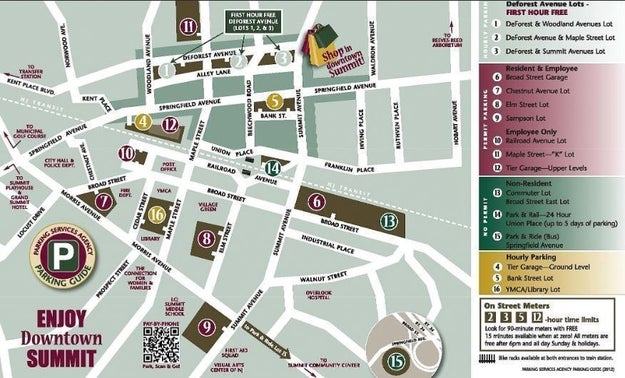

Parking near Summit’s train station is a nightmare. Commuters buy parking permits, but are not assigned spaces, and often waste 15 to 20 minutes prowling for a spot in the morning, Rogers said. But building a new parking lot to address commuter demand would be a long-term, multimillion-dollar endeavor. So Rogers reached out to Uber’s New Jersey general manager, Ana Mahony, last October and pitched an idea: What if Summit subsidized commuters’ Uber rides to the town’s train station? Priced at $2 each way, the rides would cost commuters the same as an all-day parking permit. The deal would reduce demand for Summit's hard-to-come-by parking spaces and create a steady pool of demand for Uber.

“We wanted to offer residents a convenient alternative to driving and looking for parking spaces, which can be scarce,” Rogers told BuzzFeed News. “If I could free up 100 parking spaces, that would help alleviate some of the demand and capacity constraints. One hundred parking spaces is pretty significant in our system.”

Uber was intrigued. After some discussion, it agreed to a six-month pilot program for about 100 Summit residents.

Summit is about 6 square miles, which keeps ride-hail fares within its boundaries relatively inexpensive. Residents will have to opt into the Uber pilot program, and the ride-hail company will denote their accounts for the promotion. Residents who have already purchased $4-per-day parking permits will be able to take Uber to the train station for free. Those without prepaid parking permits will pay $2 each way. Summit will reimburse Uber for the difference between the flat fares and the true cost of a ride, which drivers will receive up front.

The benefit is clear for Summit, which now can forgo massive capital expenditures on a new parking lot it would otherwise need to build and maintain. Instead, it can pay a fraction of that amount to shuttle people to and from the train using Uber. Rogers told BuzzFeed News that he expects the deal will cost Summit only about $167,000 annually, a far cry from the likely $10 million it would cost to build a parking lot — plus, Summit doesn’t have enough idle land downtown, anyway.

Via cityofsummit.org

For Uber, the Summit pilot is a new way to tap into the sprawling and unconquered US ride-hail market beyond the major metropolitan ones it dominates. While Uber and Lyft have saturated most major cities, only 15% of Americans say they have used ride-hailing services, and another 33% claim to be unfamiliar with them, according to a late 2015 Pew Research Center survey. Meanwhile, the same survey found that 21% of urban Americans say they have used ride-hail services, compared with 15% of suburb-dwellers.

Partnerships with local governments also help Uber show commuters how ride-hail can be an alternative to driving — especially if it doesn’t cost any more than parking a car in the lot outside the train station. (Los Angeles, a city synonymous with car culture, has become a proving ground for this shift.)

It helps that Summit’s affluent population is already familiar with Uber. In December, while negotiating the commuter pilot program, Summit paid for an Uber promotion that gave residents $5 rides within its borders, an effort to ease congestion and drunk driving during the winter holidays. Rogers said called the promotion “very, very successful.” The partnership worked out nicely for Uber as well: Ridership increased 300% for the month compared with the year prior, Rogers said.

Uber's partnership with Summit is one of a handful of deals with smaller cities and towns outside the major metro areas on which the company built its business. In March, Altamonte Springs, Florida, became the first town to subsidize ride-hail services for its residents. Ten miles north of Orlando, Altamonte underwrites 20% of the cost of every Uber ride within its borders; it covers up to 25% if the rider is going to or from the local light rail. Passengers need only enter “Altamonte” in the promotion-code field in the Uber app to receive the proper discount for rides within the city's geofenced boundaries. Then Uber bills Altamonte Springs at the end of the month, and the city cuts a check.

For city administrators and local transportation agencies with strained budgets, ride-hail subsidy programs like these are another solution to the so called “first and last-mile” problem: getting people to a bus or rail stop so they can ride public transportation to their final destinations.

In February, the Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority County, near Tampa Bay, Florida, launched a pilot program in which the agency covers half the cost of Uber rides up to $6 to and from designated stops near local transit centers and bus stops. And in San Francisco, the developers of Parkmerced, an apartment and townhome community, offer new residents a $100 monthly stipend toward “multimodal transportation,” including Uber.

The Summit partnership, though, offers a different spin on that model. While other cities have offered Uber or Lyft subsidies in an effort to increase ridership for public transportation, Summit is using Uber to streamline its residents’ commutes, a move that could foster a dependency on the ride-hail service in a town, where people own homes with multi-car garages and drive to get everywhere.

“It may affect decisions personally in the future, where they realize a family doesn’t necessarily need two cars,” Rogers said. “They might say, ‘You know, we used to have this second car because I needed it to go to the train station.’ And the car would just sit there.”

No comments:

Post a Comment